Sustainable Travel is Matter of Heart, not Abstract Ideas

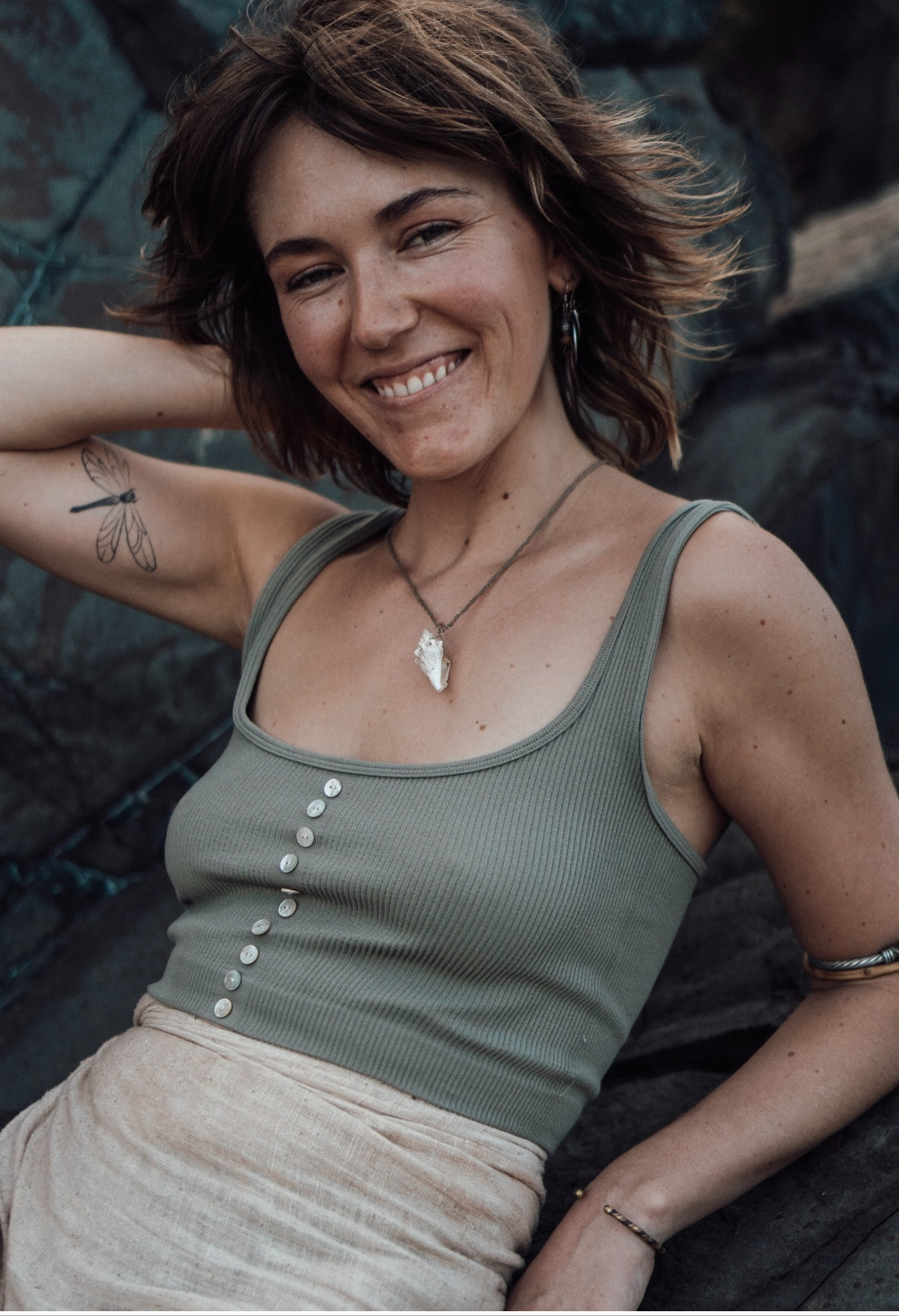

Imogen Lepere is a travel writer and journalist, born in London and living a nomadic life between her base in Devon and the rest of the world, where she immerses herself in small communities and regenerative projects. She is the author of five books about food and travel, and her evocative storytelling has earned a host of accolades — most recently, Sustainability Travel Writer of the Year 2024 at the UK Travel Media Awards.

In 2022, Imogen published The Ethical Traveller (Smith Street Books) where she compiled 100 tips aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The aim was to help fellow travellers protect the planet, support communities and explore the world, while preserving everything that makes it special. Alongside her credentials, the deep empathy and infectious energy with which she approaches every new cause, place or community leave no doubt — when it comes to travelling more mindfully, Imogen is an expert. We caught up with her to discuss how she reconciles her love of travel with her commitment to sustainability, and how we can all learn to travel better.

Inspire editionWhen did you first decide you wanted to write about travel? And why community-led tourism, specifically?

Imogen LepereI think the most formative trip of my life was when I went to Nepal on my own at the age of 18. It was my first time travelling solo. Even by my standards today, it was quite an extreme trip; I didn’t know anyone, there was no phone signal, and I got into all kinds of trouble. Luckily, I met only lovely people who really looked after me and they were all local — I barely met any other travelers the whole time I was there. I spent six months in very rural areas in the Himalayan mountains, and that’s where I had this moment that has remained with me ever since. I had a holiday romance, and at one point, I found myself shopping for underwear. I went into this tiny wooden shop where everyone was wearing traditional clothes. When I tried to explain what I was looking for, all the women in the shop got involved, gesturing for me to try things on. It turned into a surreal, shared experience.

That trip taught me that, no matter how different things look on the surface, it always comes back to human connection — and we are much more similar than we are different. I wrote a story about that experience, which won a competition for young female writers in The Telegraph. That’s where it all started!

IEBeautiful story! Since then, in your subsequent years of travel, what is the place or community project that has impacted you the most?

ILI would say it’s the Ibity project in Brazil. I only spent a week there, but it left a huge impression on me. It’s an interesting example of an alternative view on what value is. The project is on privately owned land, run by a multimillionaire named Renato Machado, who takes profits from his other businesses and invests theminto rewilding this piece of land. The soil is so degraded by intense cattle farming that even grass won’t grow anymore, so there’s not much employment for local people. Before the project started, many young people were forced to emigrate to cities, but some are now returning.

What’s radical is that once the project becomes profitable, he plans to sell the land to the local community, with no individual owning more than 1%. It’s an incredible model for rethinking value systems that aren’t based purely on money. So yeah, I’d choose this project as it feels larger in scope than many others I write about and it shows what’s possible when community-focused tourism operates on a bigger scale. There’s something there that other businesses and projects can really learn from.

IEA question you must get asked a lot: can travel ever truly be sustainable?

ILAs a journalist, I see my job as asking questions rather than giving answers, but here’s where I’m at right now…

It’s complicated. Travel is part of an extractive capitalist system that’s causing the climate crisis — no doubt about that. At the same time, the tourism industry accounts for 1 in 10 jobs globally, making it the biggest employer in the world. Would the world be a fairer or more sustainable place if the industry disappeared overnight? I don’t think so. Many of these jobs are in remote places, and without tourism, people would have to turn to extractive industries like logging or mining.

I’ve also seen so many examples of travel being used as a force for sustainable development. There’s a type of travel that centres locals and the environment rather than the tourist, and it works.

When people talk about travel as a “guilty pleasure”, I feel strongly resistant to the idea of guilt or shame — like flight shame. I think people respond better to joy, excitement and inspiration. Meaningful connections with people and ecosystems touch your heart in a way that abstract ideas can’t. I think travel offers us a unique way to feel a sense of shared stewardship for our home — the earth, and each other.

IEAs a general rule, what advice would you give to fellow travellers who want to support the local communities they visit rather than disrupt them?

ILI think one of the best things you can do is choose projects that are owned and operated by the community itself. Even if you’re booking through a tour operator as part of a wider itinerary, ask questions or do your own research. Who’s running the experience? Is it the community, or is someone from the outside managing it?

Showing a genuine interest in their culture and traditions is also powerful. Many Indigenous communities are in the process of rediscovering their own traditions. For example, in Mexico, I’ve seen younger generations learning traditional languages from their grandparents because their parents didn’t grow up speaking them. Tourists showing interest — wanting to learn words in the traditional language or asking about customs and rituals — can help communities value and reconnect with their own heritage.

Another thing is to adjust your expectations. Community-led tourism isn’t an off-the-shelf product. The experience will likely be different from what you’re used to, including communication styles or a different understanding of time, which may not fit your culture’s service standards. And, importantly, accept when they say no. If you ask to see something and they say no, respect it — they will share what they want to share and keep private what they want to keep private.

Finally, make it a meaningful exchange. Maybe share pictures of your home or your family with them too. When I interview people, I often ask if they have questions for me. I think people forget to do this, but it can create a lovely and more equitable interaction.

IEHow do communities usually react when you engage with them on that human level?

ILIf you go to a well-run project where they genuinely need visitors and the profits are shared fairly, rather than one that’s oversaturated with tourist groups, they’re thrilled to have you. They’re proud to share their traditions.

IEIn your book ‘The Ethical Traveller’ you explore 100 ways to tread lightly when exploring the world. What are your top three tips for conscious travellers on this?

ILI’m going to cheat and combine two into one: think carefully about when and where you travel.

For where, travel can be an incredible way to redistribute wealth directly to people who need it. For example, after the earthquake in the Atlas Mountains and Marrakech, locals have worked hard to rebuild but visitors haven’t returned. There’s no reason not to go — it’s safe now, and they desperately need tourism income.

As for when to travel — go outside of peak seasons. This doesn’t just give you a cheaper, better experience but also supports locals year-round. Seasonal gig work doesn’t allow communities to thrive.

The third tip is to keep as much money in the local economy as possible. If you fly with international airlines and stay in international hotel chains, economic leakage can be as high as 90%. That means only 10% of your holiday spending benefits the local community. To avoid this, make sure you stay at locally owned businesses, eat at local restaurants, and buy directly from artisans. It’s more rewarding for you and better for the people you’re visiting.

IEWhat inspires you most right now?

ILAlways people. I just love people! That’s what helps me centre and gives me hope. So when I feel guilty about my carbon footprint, I remind myself of the purpose of my work: providing a platform that allows people and places to reveal themselves to readers. It’s about reminding us of our shared humanity and cultivating empathy — if we truly see each other as equally human, we’ll care for each other, and for our shared planet. That’s the purpose of storytelling and why it is so powerful. I don’t want to tell readers what to think or do; I want to touch their hearts and leave it up to them.